Blog

Today marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. To commemorate this special occasion the West Highland Museum has been publishing a series of articles written by scholars, academics, authors, and Jacobite enthusiasts throughout December. In this fourteenth in the series West Highland Museum Curator Vanessa looks at the Top 10 best Bonnie Prince Charlie object in the museum’s collection.

The West Highland Museum's Top 10 objects relating to Bonnie Prince Charlie

1. THE SECRET PORTRAIT

An anamorphic hidden painting of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788). At first glance the object appears to be a smear of oil paints on a black wooden board, but when paired with a mirrored cylinder, the true nature of this unique object is revealed. Prince Charlie is reflected right back at you! Discovered by chance in a London junk shop in 1924 and purchased for £8 by the museum’s founder, Victor Hodgson, it has been a star object in our collection ever since.

In the 18th century it was treasonable to support the exiled Stuart dynasty, so their supporters known as Jacobites, devised ways to secretly display their loyalty. They developed an elaborate series of codes and symbols to hide their allegiances from the ruling Hanoverian regime. This is one of the most unusual examples of Jacobite material culture. The portrait would have been used to drink toasts to the exiled Prince. If a non-Jacobite came into the room, the cylinder could be whisked away and allegiances hidden.

2. HOLYROODHOUSE BALL FAN

.jpg)

A paper and ivory fan depicting Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788) with the Mars, Roman god of war, and Bellona, Roman goddess of war. They are surrounded by other classical gods. The figures to the right are reputed to be the family of the Hanoverian King George II fleeing.

This design is by tradition attributed to Robert Strange, the Jacobite engraver. These fans were said to have been distributed to ladies at a ball at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh in 1745. Prince Charles held the ball to celebrate the Jacobite victory at the Battle of Prestonpans.

3. JACOBITE GLASS

A fine example of a mid-18th century drinking glass with an air twist stem, engraved with Jacobite symbols. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuart dynasty was an important part of Jacobite secret culture. Jacobites would often pass their glass over a water bowl to toast their “King across the water”. Another popular toast was “to the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat,” which was a reference to William of Orange’s horse tripping over a mole hill. The fall caused him to break his collar bone and he subsequently died when he contracted pneumonia.

The Jacobite symbols engraved on this glass are typical. The six-pointed star represents royalty. A rose signifies James VIII (II of England, 1688 - 1766) and buds represent Prince Charles Edward (1720 - 1788) and his younger brother, Prince Henry Benedict (1725 – 1807). The motto “Fiat” translates as “Let it be” as in let it be a Stuart restoration to the throne.

4. THE STRANGE PLATE

An 18th century copper printing plate commissioned by Prince Charles Edward Stuart in 1746 at Inverness on the eve of the Battle of Culloden. Designed and etched by the artist Robert Strange, the plate is completely unique and was intended to be used to print bank notes during the 1745 Rising, but was never used.

When the Jacobite army was defeated at the Battle of Culloden, the army fled and the plate was found abandoned at Loch Laggan. It was presented to Clan MacPherson and remained in their care until the museum purchased it in 1928.

5. PRINCE CHARLES' TOOTH

.jpg)

A tooth mounted in a hand-carved ivory frame. The tooth is said to have belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart. It is very rare and thought to be the only known example of a tooth from the Prince in any museum collection.

The tooth is barely worn and would suggest it was probably removed from him as a child. It was gifted to the museum by the Fairfax-Lucy’s of Callart House in 1975.

6. THE PRINCE'S TREWS

.jpg)

Royal Stewart sett hard tartan trews with integral 'feet'. Traditional trews were not trousers, but long hose which were worn high up to the waist. These are puported to have belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart.

The trews are special not just because of their connection to the Prince, but because they were one of the earliest objects to come into the museum’s care in 1925. In 2003/4 the trews were loaned to Museo del Tessuto, Prato, Italy for an exhibition.

7. THE PRINCE'S WAISTCOAT

A pale green striped silk waistcoat that has been embroidered with rosebuds and silver thread. It is a textile with a fascinating history. The waistcoat once belonged to Prince Charles Edward Stuart. It was quite common for Charles to gift his personal belongings to supporters as souvenirs.

However, the gifting of his personal clothing is fairly unusual and would have only been bestowed upon his most trusted friends and confidants. In this case the provenance of the waistcoat can be traced. Charles gifted this waistcoat to his doctor, Doctor Irwin, before he left Rome in 1744.

8. HIDDEN PORTRAIT SNUFF BOX

3.jpg)

A circular box with an enamel tartan decoration. The hinged cover opens to expose a plain interior. However, the hidden double lid opens to reveal a finely enamelled portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart dressed in a tartan jacket with the orders of the Garter and Thistle decorations, white cockade and blue bonnet.

Hidden portrait snuff boxes such as this are amongst the most iconic Jacobite works of art. This example is in particularly good condition and finely enamelled. The portrait is a variant of the famous Robert Strange example which likely date this piece to circa 1750. Purchased in 2019 with the assistance of the Art Fund and National Fund for Acquisitions.

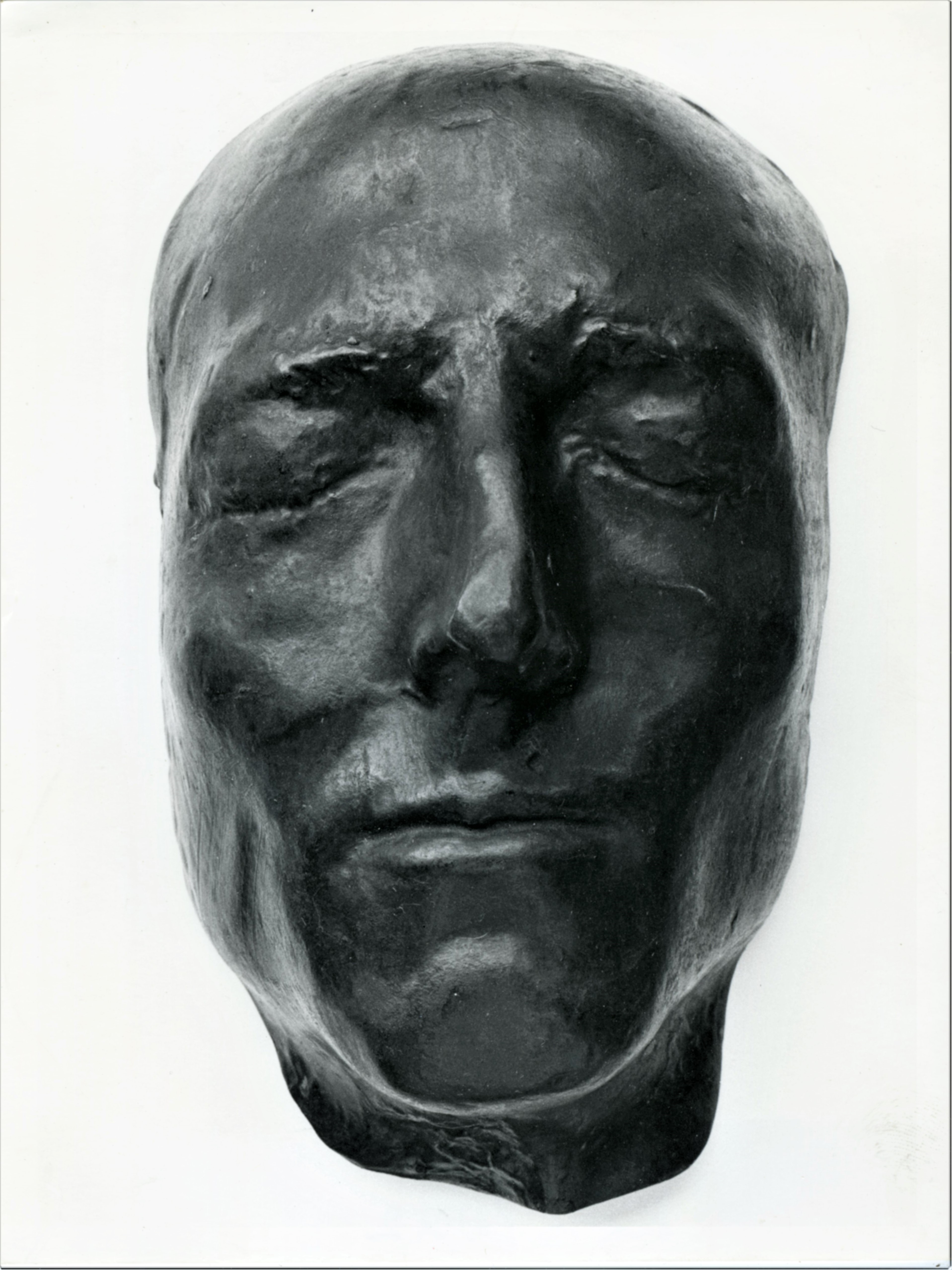

9. DEATH MASK

Prince Charles Edward Stuart's death mask. Thought to be a copy of an original made by Barnar dina Lucchesi, one of a family of modellers in Rome. brought this mask to Scotland in 1839. The mask had been handed down through his family. Lucchesi settled in Glasgow where he continued to work as a modeller until 1863. Lucchesi fell on hard times and some of his belongings, including the mask, were sold.

Eventually the mask ended up being purchased by a sculptor named Ferguson. When it came into Ferguson's possession it was said to have hairs attached adhering to the eyebrows and eyelids! This bronze cast of the death mask came into the care of the museum in 1951 courtesy of the Scottish independence campaigner Wendy Wood.

10. TREE ROOT STOOL

This unimposing curved stool made from a tree root has a fascinating history. A label attached to the object states “Stool on which Prince Charlie sat when in hiding in Uist after Culloden.” It was given to the pioneering Victorian folklorist Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912) by Rachel MacDonald, the great granddaughter of Morag MacDonald.

Legend has it that three sisters living on a croft on Uist provided food to Prince Charles Edward Stuart one evening when his party passed through the area when they were on the run from Hanoverian troops in 1746. When the sisters realised who their visitor was, they quarrelled as to whom should keep the stool. Morag won the fight and the stool became a treasured family heirloom, until it was gifted to Alexander Carmichael. Part of the Carmichael Collection is now in the museum’s care, while his archive is in the care of Edinburgh University.

Vanessa Martin