Jon Schueler (1916-1992)

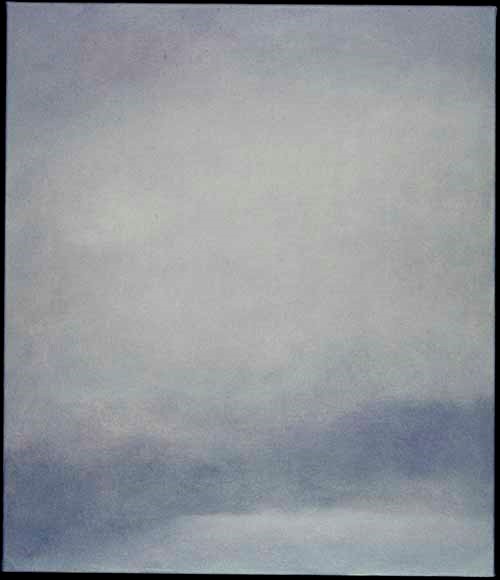

Snow Cloud: Sun and Sleat, I, November 1974 28 x 24 in/71.12x 60.96 cm, oil on canvas (o/c 379)

Collection: The West Highland Museum, Fort William, Scotland

This work is one of six Schueler paintings in the Snow Cloud: Sun and Sleat series, all from 1973 -1974 and all small – ranging from this one, the largest (28 x 24 inches), to the two smallest ( 8 x 10 inches). They were all painted in Jon Schueler’s Scottish home and studio called Romasaig which was formerly an old schoolhouse in Glasnacardoch, a mile outside Mallaig, Inverness-shire.

Romasaig, with its gable end to the sea to protect it from the fierce winds coming in from the Sound of Sleat, so his studio (the former classroom) looked out on to the hillside of the promontory, frequented only by sheep. Going out into the weather for a walk, Schueler first experienced the views across the Sound of Sleat to the Armadale Peninsula on the Isle of Skye. Every moment of every day was different, revealing or hiding the contrasting shapes of the Black and Red Cuillins. Then crossing the stream, the islands of Rhum and Eigg, and on occasions Muck and Canna gradually appeared. The further the walk, the greater the expanse of the Sound, the greater the variations in light, the deeper the immersion in elemental nature.

Jon Schueler’s preoccupation with the snow clouds stems from his first visit to Mallaig during the autumn and winter of 1957-58. In his memoir The Sound of Sleat: A Painter’s Life (published in 1999), he describes the occasion (pp. 61-62):

““…In early January I spent an afternoon on a peninsula jutting into the sea. The snow clouds, opaque, sometimes ghostly, sometimes full of fire and life as they reflected the light of the sky and the low winter sun, moved across the Sound of Sleat, pushing down to the sea like curtains, forming new horizons. Sometimes I would watch them as they approached, finally engulfing me in snow driven almost horizontally at me by the force of the wind, so strong that I would have to take cover behind a hillock. Then for a while I would be blinded in the middle of the snow cloud — until it passed, suddenly and swiftly, and I would be in the clear air again watching new clouds form far away, slowly obliterating islands on the distant horizon, a horizon that could have been real. At one moment I turned and looked and saw the sun glowing dully through a snow cloud. In the following weeks I painted some snow cloud studies, and then some major works, of which this is one.

I felt that the juxtaposition of sea, land and sky, of the cloud and the sun, all in motion against each other and reflecting each other, suggested the possibilities of infinite nuances of human emotion and of the emotion of time…”

This memory remained with Schueler always, and in the Snow Cloud: Sun and Sleat series, there are hints of land, glimmers of light from the sun, the movement of weather passing through and over, and the acknowledgment of the tremendous power of nature — even in its tenderest and most elusive form. These indeterminate visual layers feed into the viewer’s own experience and memories of looking into the mysteries of the northern skies.

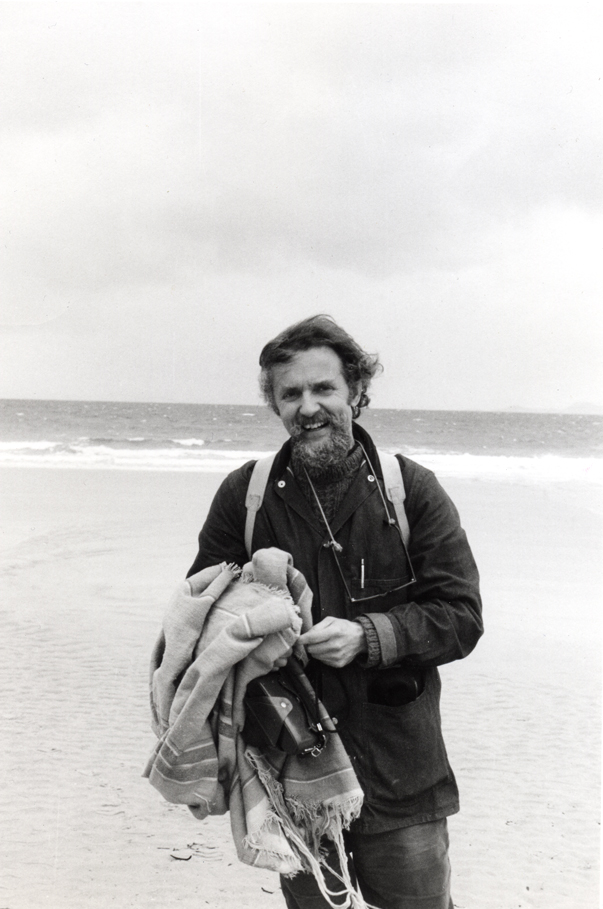

Schueler lived in Mallaig continuously from 1970 to 1975. Although then shifting his base back to New York, he still returned almost every year for several months – the Sound of Sleat a necessary touchstone for him, a direct connection with the source.

Magda Salvesen

New York. 8 January 1960.

Excerpts from “A Letter About the Sky” by Jon Schueler published in It is, Number 5, Spring 1960[1].

“When I speak of nature I’m speaking of the sky, because in many ways the sky became nature to me. And when I think of the sky, I think of the Scottish sky over Mallaig. It isn’t that I think of it that nationally, really, but that I studied the Mallaig sky so intently, and I found in its convulsive movement and change and drama such a concentration of activity that it became all skies and even the idea of all nature to me. It’s as if one could see from day to day the drama of all skies and of all nature in all times speeded up and compressed. I knew that the whole thing was there. Time was there and motion was there — lands forming, seas disappearing, worlds fragmenting, colors emerging or giving birth to burning shapes, mountain snows showing emerald green; or paused solid still when the gales stopped suddenly and the skies were clear again after long days of howling sound and rain or snow beating horizontal from the sky….

“The sky. Father and Mother and Mistress, and the lonely mystery of endless love. Eternal Fact, felt through the emotion of its change, the weather patterns moving fast and slow across the sea and points of land, beating against one’s face when the snow cloud funneled through the valley, pressing one relentlessly when the gale winds moved like a visual force through the day sky or the sky of night. The sky was multiform, as complex as all life…

“I found every passion in the sky — as encompassing and as certain and as fleeting as the intimacy of a night mist. This passion — this daily awareness of a mistress who is always there, who is there without fail even in the violence of some moods — this sensation of being was always the life behind any sudden glimpses of esthetic mysteries or any wanderings of the intellect across the horizon or past the shadow of the sea. Humanity was there; my heart was never so concerned with man, I like to think. The sky was not a substitute for man. It was an enlargement of man. And there was always the mystery behind the discovered. There was always a passion and a mind above and beyond that which one felt and understood. And therefore, in the mind of the artist, there was always a loneliness, a sense of reaching, of seeking, of never quite finding it all, of never having it all in his grasp, of never knowing, really, and then coming back to himself alone, to his work, to the canvas in the claustrophobic house, to his scratchings, to his effort, to his mark….”

The Sound of Sleat: A Painter’s Life by Jon Schueler, Picador USA, 1999, pp. 65-66

[1]Edited by Philip Pavia, It is was a magazine primarily devoted to artists’ writings and statements. There were five issues between 1957 and 1960 and one later.