2022 marks the 300th anniversary of Flora MacDonald’s birth. With it comes the opportunity to honour her life and her bravery, in assisting Prince Charles Stuart and his escape from British justice following the calamity at Culloden.

This year the West Highland Museum, like the West Highland landscape in 1745, will be a hotbed of Jacobite activity, as the museum commemorates the return of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the exiled Stuarts (in the form of a series of rarely seen and iconic 18th century paintings). In addition to the exciting new exhibition, the Museum marks its 100th birthday this year, and, of course, the 300th anniversary of Flora MacDonald’s birth, complemented by the Museum’s unique collection of pieces associated with Flora.

It seems that – even three centuries after her birth – the contribution of the young lady from the Isle of South Uist will not be easily forgotten. But has such interest in the importance of Flora MacDonald’s contribution to Scottish history always been the case? In researching some elements of her contribution in the escape of the Prince during 1746 (for a future book), I stumbled on an interesting piece from the London Illustrated News, dated 27th January 1872 and written with reference to the 150th anniversary of Flora’s birth. It seems that the respected periodical had previously lamented the absence of a worthy memorial to the lady (in an editorial written in 1868) and were delighted with the resulting outcome.

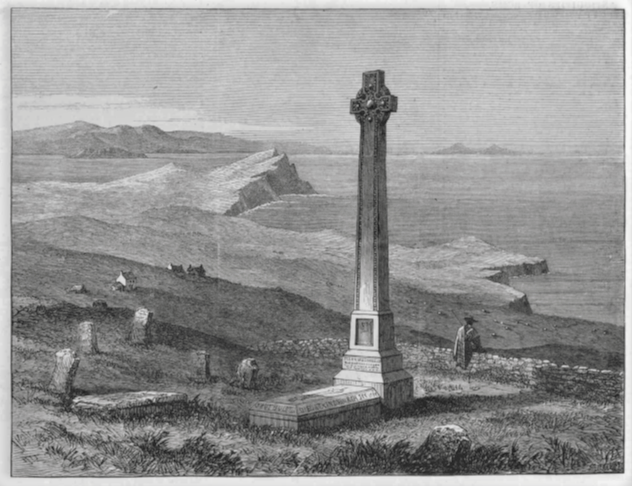

For your interest, I have carefully transcribed and edited the piece, and reproduced a sketch of the rarely seen line drawing that originally accompanied the article:

FLORA MACDONALD.

Rather more than three years ago, writing about some point of interest in the Isle of Skye, we took occasion to comment upon the fact that no memorial stone of any kind marked the burial-place of Flora Macdonald. Hers is the only historical grave which it was left to the islanders to honour and protect; and, as the late Alexander Smith pointed out, it was shamefully neglected.

(Alexander Smith was a well-known Scottish poet, best known for his work A Summer in Skye, who had passed away from typhoid fever five years earlier.)

Our remarks had more effect than we could have anticipated; they were taken to heart in the right quarter, and, through the instrumentality of the young northern chief, Mackintosh of Mackintosh, backed by another northern potentate of modern growth, the Inverness Courier, the handsome monument has been successfully erected over the grave of the heroine. With great difficulty, arising from the ponderous character of the monolith and the abruptness of the road over which it had to be carried, the monument was placed, in November last, in the presence of the lord of the manor, Mr. Fraser of Kilmuir, and about 400 Highlanders, who stood unbonneted around the grave. In justice to the distinguished family of which Flora Macdonald was a member, it should be stated that her son, the late Colonel John Macdonald, of Exeter, sent a marble slab to be placed in the burying-ground, but it was broken in the course of transport, and was literally carried away piecemeal by tourists.

I wonder how many people on the Isle might claim to be in possession of a shard of that marble slab, perhaps handed down to them by their ancestors? Or, indeed, own a mysterious piece of that smooth material; of which they have no clue as to its original purpose or origin.

Quite recently another descendant, also a Colonel Macdonald, commissioned a monument at his own charge; but before it was completed the present larger and more national monument was begun, and superseded its necessity. The Iona cross which now stands in the churchyard of Kilmuir on Syke is a monolith of the finest grey granite, prepared by Mr. D. Forsyth, of Inverness, from a design by Mr. Alexander Ross, the architect of the Inverness cathedral. As compared with the great historical crosses which have survived from ancient times, this one is very much larger. It is 28 feet 6 inches high, the cross itself being a monolith no less than eighteen feet and a half in height. The celebrated Inverary cross is only 8ft. 6in.; Maclean’s cross, at Iona, 11ft.; that of Oronsay in Argyleshire, 12ft.; St. Martin’s, 14ft.; Gosforth, in Cumberland, 14ft. 9in., and that of Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, 16ft.

The monument occupies a most commanding position at the extreme northwest of the Isle of Skye, within a few miles of the ruins of Duntulm Castle, the original seat of the Lords of the Isles, who at one time dominated over half the western seaboard of Scotland and threatened even the stability of the Scottish throne. The coast is singularly bold and picturesque, being, in common with the whole of the great promontory, or peninsula, composing this part of Skye, of landslip formation, the strange and picturesque peculiarities of which receive their highest development in the rocks of the Quiraing and the Storr, which are only a few miles distant.

The Quiraing forms part of the Trotternish Ridge escarpment on Skye and, even today, the landslip still moves, necessitating regular road repairs at its base.

The service rendered to Prince Charles Edward by Flora Macdonald —for which her name lives in history, and for which, according to Dr. Johnson, “it will ever be mentioned with honour, if courage and fidelity be virtues” —is very well known. After the disastrous battle of Culloden, on April 16, 1746, the Prince fled from one hiding-place to another, with the price of £30,000 upon his head. As he had landed on the west coast, knowing that among the Highlanders there he should find his most devoted adherents, so he now sought refuge among them, not less on account of the mountainous and difficult nature of the country than because he could trust his life there, even among people who, by the peculiar character of the system of clanship in the Highlands, were nominally his enemies.

Some of the great clans, and conspicuously the chiefs of the Macleods and Macdonalds, took an unfavourable view of the chances of the rebellion from the outset, and they refused to call out their men in his support; but at heart the whole mass of the people were favourable, and the idea of betraying the Prince, even for such a sum, was utterly repugnant to the fervid loyalty of the clansmen of that time.

When Mr. Macdonald, of Kingsburgh, was reminded by the officer who examined him, as to the part he had taken in helping to effect the Prince’s escape, that he had lost a noble opportunity of “making himself and his family for ever,” the Highlander resented the speech. “A mountain mass of gold and silver,” he said, “could not give me half the satisfaction I had from doing what I have done.” Eheu! Are there men of this mould now?

“Eheu” is a lovely Latin expression of pain and regret, meaning ‘Alas’, which has sadly slipped from our language.

Returning to the London Illustrated News article:

While 1500 militia were scouring South Uist in quest of the Prince, more than a hundred of the islanders knew where he was in hiding; but none of them gave a hint on the subject to parties unfriendly to him, and it was the same in all parts of the Highlands where he was secreted. The Prince had been thus screened for more than two months, when at length the search for him in the outer Hebrides became so minute that escape seemed hopeless. The soldiers received instructions to explore every nook and cranny of the island, and the Prince had to separate himself from all the companions of his wanderings, except his faithful friend Captain O’Neal. It was in these trying circumstances that Flora Macdonald resolved to attempt his rescue. Various circumstances contributed to point to her as the only person suitable for the enterprise. Flora was at the time on a visit to her brother in South Uist, but usually resided with her mother and step-father in the Isle of Skye. She was on intimate terms with the family of Clanranald, to whom the movements of the Prince were well known, and it happened that her stepfather was in command of one of the independent companies of soldiers stationed in the Long Island.

To avoid unpleasant encounters with the soldiers, who were ransacking every house and hovel of the district, Flora applied for leave to return to the house of her mother, in Skye, and obtained a passport for herself and servant, and also for a young Irish girl named Betty Burke, whom she wished to take home on account of her skill in spinning flax. The Irish girl was no other than the Chevalier, and his servant, Neil Macdonald.

The second part of this article from 1872 and the artifacts that link this story with the West Highland Museum will be continued.

Mark Bridgeman

Mark Bridgeman is an author. His book “Blood Beneath Ben Nevis” is available at West Highland Museum. A full range of his books are available at Waterstones & on Amazon.

Mark Bridgeman’s Facebook page