During the lockdown of 2020 I wrote a series of articles, about the remote and unique island archipelago of St Kilda. Somehow the isolation of lockdown matched the mood of the islands. Perhaps the most poignant piece was the story of islands’ mass evacuation in 1930.

Following years of hardships, depopulation, food shortages, disease, and growing feelings of isolation, the remaining 36 residents finally and reluctantly recognised that life on St Kilda could no longer continue. On 10th May 1930, twenty of the islanders petitioned the British government, pleading for resettlement on the mainland. With most of the able-bodied young men already left to work in Scotland the heart-breaking plea read, ‘it would be impossible to stay another winter’. .png)

After months of discussion, government penny-pinching, and cautious questioning, the 36 remaining residents were finally evacuated on 29th August 1930. The islanders’ homes were locked up, and the HMS Harebell steamed eastwards away from St Kilda carrying the 13 men, 10 women, and 13 children that made up the remaining population of the islands. The Harebell’s Commander later recalled the mood of the islanders, ‘Contrary to expectations, they had been very cheerful throughout, though they were obviously very tired.’

However, a different account reveals that the residents left the 11 remaining homes on the island like ‘an open grave, doors unlocked, with a small pile of oats and an open bible left on the tables’, as if they had merely stepped out for the day.

Once on the mainland the ex-residents of St Kilda were exposed to a multitude of new experiences – such as the motor car, the wireless, and even seeing a tree for the very first time. Meanwhile the new owner of St Kilda, the Earl of Dumfries, received many requests from people who wished to move to the islands, but he always refused. Just as the evacuated islanders had come to appreciate, the Earl also accepted that a 19th century style existence on St Kilda was no longer possible in the 20th century.

Nevertheless, this was by no means the end of the exiles’ association with the islands. For many years several former islanders made a summer pilgrimage to Hirta (the main, and only previously inhabited island), partly to reminisce, partly to recuperative from the common colds they appeared to regularly pick up on the mainland (from which they oddly seemed to have no immunity), and lastly as tourist guides.

It is not commonly known, however, that a group of ten St Kildans actually returned to live on the bleak archipelago in the summer of 1935 for a rather unusual reason. The group’s return to St Kilda also very nearly ended in disaster . . .

When the SS Hebrides departed from Glasgow on Thursday 30th May 1935, it contained a party made up of representatives from four of the five families originally evacuated from the island in 1930. Fergusons, McQueens, Gillies, and MacDonalds were onboard. Only the MacKinnons were unrepresented, due to a recent family bereavement. The party was joined by Earl of Dumfries, the islands’ owner, and the photographer and filmmaker Niall Rankine. The St Kildans, who had previously refused to give permission for their evacuation from the islands to be filmed, were now going to ensure that St Kilda would live again, if only on the screen.

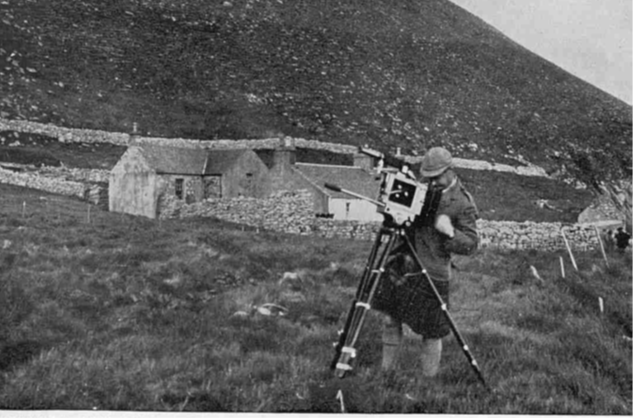

After several delays, caused by the worst storms for 40 years, the vessel eventually managed to land its passengers on Hirta. This time the group was well prepared. The Earl of Dumfries has provided a 14 ft motor boat for easier transportation between the two outlying islands. The visitors were lodged at the old manse and in one of the other remaining dwellings on the island. The Earl, who had purchased the island primarily as a bird sanctuary, had brought the group back to St Kilda for the two purposes. Firstly, the intention was to study, ring, and film the countless varieties of sea birds that nested on the archipelago. Niall Rankine shot over 5,000ft of film during the course of the visit, including some distinctive images of the islands in their uniquely transitory state between occupation and later development for other purposes. The St Kildans assisted Rankine with his photography and filming. Apparently, they had become accustomed to the camera in the five years since the evacuation.

Secondly, the islanders intended to weave a special tweed (to be later tailored into a suit) as a jubilee gift for His Majesty King George V. The King had expressed an interest in receiving the tweed and the islanders felt honoured to undertake the task. The unique tweed was to woven from the wool of the island sheep, under the direction of Mrs Ghillies, the uncrowned ‘queen’ of St Kilda. Upon their return to the mainland the tweed would be presented to the King at a special ceremony.

Unbeknown to the King, however, was the extraordinarily difficult and dangerous travails involved in collecting the wool from the ancient island flock of Soay sheep. Mr Neil Ferguson, the island’s former postmaster, explained,

‘The sheep on Hirta and Soay will have to be rounded up and cornered, in order to lay hold of them. They are now wild and frightened and think nothing of leaping high into the air over your head. The rams are particularly aggressive too. Also, the sheep are not white woolled; they are more or less brown and black in colour. Natural dyes, but mostly crotal (a yellow lichen, common in the Hebrides), will be used to bring the wool to the right shade, after which it is carded, spun, and mixed to give the blend required.’

Even with the use of the Earl’s motor boat, the journey to the other islands to trap the flock became fraught with danger as the storm intensified,

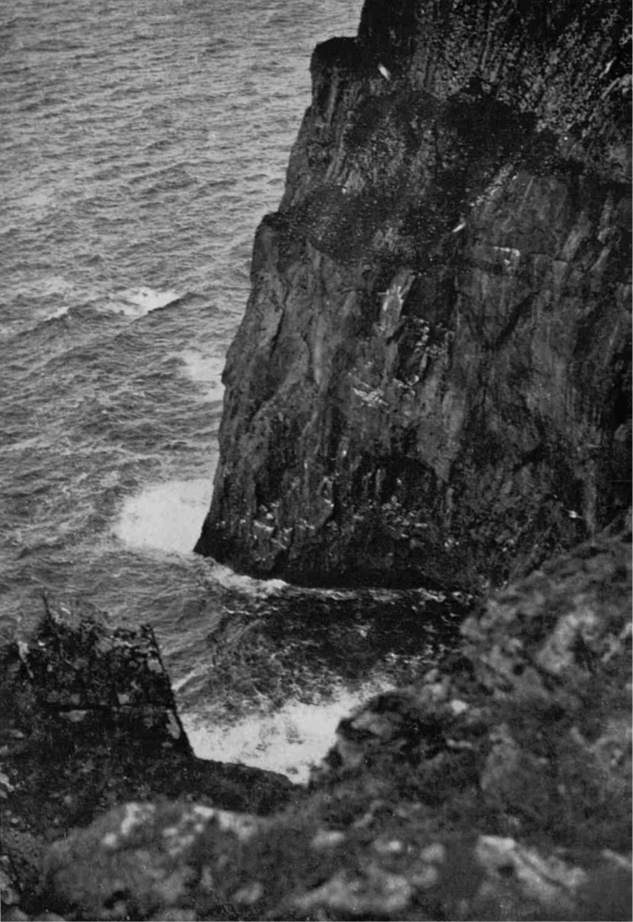

‘The sound of the Atlantic rollers breaking on the rocks round the island’, as described by Neil Ferguson, ‘is the only sound we can hear, apart from the screeching of the birds. But this year the weather is wilder than it has been for forty years, our ears are resounding to the thunder of the waves as they dashed themselves on the rocks near the village on Hirta, and as they licked greedily on the cliffs behind us. Out at Bororeagh, the grim island which stands like a sentinel in the Atlantic guarding the approach to the main island, tumultuous seas leapt hundreds of feet high against the grey cliff sides of Stac Lee, the 1,300 ft high rock which stands bare and barren next to Bororeagh, its spume and spray flicking ledges which normally were safe from the water. It was one of the most awe-inspiring experiences of my life.’

If the dangerous and life-threatening storm was not enough, a near tragedy almost blighted the small group’s time on the island of Hirta. Neil Gillies (a natives of St Kilda) had undertaken to clear away the remains of some huts built on the island by the British Government during the Great War. He had successfully demolished one and lit a bonfire to burn the wreckage, when there was a sudden and huge explosion. Neil, who was stood less than 12 yards away, was knocked to the ground by the force of the blast. Boulders and stones were thrown hundreds of yards in all directions by the explosion and the windows of the church and manse were shattered. It was the loudest noise ever experienced on an island constantly pounded by the ravages of Atlantic storms and breakers.

Neil Gillies miraculously escaped without serious injury. The only possible explanation seemed to be that an enemy artillery shell had lain buried there since a German U-boat raid on St Kilda during the Great War.

The story of an attack by a German submarine in 1918 was generally kept quiet, to avoid public discontent, at a time when the Allied forces hoped to be bringing the war to an end. However, it was discussed in parliament a year later, as this extract from Hansard reveals,

‘Wednesday 28th May 1919

Dr. Donald Murray asked the First Lord of the Admiralty whether he “is aware that a considerable number of the buildings on the island of St. Kilda, including the church and the nurse’s house, were destroyed by shell-fire from a German submarine last summer; and whether the Government propose to pay compensation with a view to restoring these buildings?”

The President of the Board of Trade (Sir Auckland Geddes) in response:

“My right hon. Friend has asked me to answer this question. I am aware of the facts stated in the first part of the question. I am sending the hon. Member a copy of the Air-raid Compensation Scheme, and if the circumstances of the damaged property comply with the conditions of the scheme the owners will be entitled to compensation. I may mention that compensation has already been granted by the Air-raid Compensation Committee in three cases at St. Kilda and four other cases are under investigation”.‘

Whilst the explosion may have been caused by an unexploded German shell, it was also possible that the explosion had resulted from a consignment of gelignite left over from a long-forgotten blasting operation on the island. Whatever the reason, St Kilda almost claimed yet another victim during mankind’s struggle to eke out an existence in this harshest of environments.

Neil Gillies (apparently none the worst for his adventure) together with one other native of the islands, decided to remain on Hirta longer than the other ex-St Kildans. They waved goodbye when the SS Hebrides steamed away, carrying the remainder of the group safely back to the mainland. It is difficult to imagine the emotions and sensations that the two men must have experienced, as their link with civilisation vanished into the mist, away to the east, leaving the two men to a life there had left so suddenly five years earlier. Now settled on the mainland, into a new world of electricity, cars, radio, and cinema, did they find the ghostly remains of the town on Hirta an alien and unbearable experience? Or perhaps they secretly yearned for a return to a time that had long since passed?

The pair returned to the mainland on the last tourist ship to visit St Kilda, at the end of the summer season in August 1935. The islands, once again, resounded only to the cries of fumars, puffins, and the relentless bleating of the Soay Sheep, as the perilous seas of winter pounded its isolated and dizzyingly high cliff faces for yet another menacing Atlantic winter.

Despite the remote location and the harsh nature of St Kilda, its draw to visitors remains as magnetic today as it has since the first curious Victorian tourists began to arrive 150 years ago. For Neil Gillies, born and bred on the island, the compelling wish to return lingered deep inside him for the rest of his life.

Neil passed away in 2013. The final surviving resident of St Kilda, Rachel Johnson, died in 2016 at the age of 93. She had been only 8 years old at the time of the evacuation. At the moment of her passing, the compelling and magnetic emotion to return to the island, known only to St Kildans, disappeared too.

As outsiders, we can all sense the strange attraction that the island offers, although I suspect it is a very different sensation.

Mark Bridgeman

Mark Bridgeman is an author. His book “Blood Beneath Ben Nevis” is available in the museum’s shop.