The 31st December 2020 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. To commemorate this special occasion the West Highland Museum has organised a series of articles written by scholars, academics, authors, and Jacobite enthusiasts. In this thirteenth in the series author Mark Bridgeman, focuses on incidents in Brampton during the 1745 Rising that were remembered in the Carlisle Patriot in the19th century.

Prince Charles Stuart at Brampton in 1745

During some research I had undertaken recently, I stumbled across a long forgotten article from an obscure regional newsheet, the (rather pointedly named) The Carlisle Patriot. Dealing, as it does, with two of the less well known and discussed incidents in Prince Charles Stuart life, the 300th anniversary of his birth seems the perfect time to share these episodes. The story contains directly remembered and ‘handed down’ passages of dialogue from witnesses to the events. Since ‘Living’ eyewitness history’ provides such a valuable lens into the past but, by its very nature, fades from memory as those who impart it also fade, the current commemoration of his life seems the perfect time to rediscover these recollections of the Bonnie Prince.

The subject of the article is a report on a lecture given by the Rev. H. Whitehead of Newton Reigny, in Cumbria, to the members of the Carlisle Scientific Association, at a packed Carlisle Museum, on Tuesday 22nd March 1887.

‘The Lecturer said—When, on Tuesday November 10th 1745, Prince Charles Stuart was about to begin the siege of Carlisle, hearing that Marshal Wade was expected from Newcastle, changed his plans; determining to march eastward, so as to engage the English on hilly ground, his Highlanders being accustomed to such ground. Next morning, therefore, he marched with his army to Brampton; where, having probably intended to stay but a single night, he remained a week – more than twice as long as he had stayed anywhere else in England, and a sixth part of the whole period of his campaign on this side of the Border. “They came down the Lonning”, said David Latimer, “and they took possession of the chapel of the Alms Houses. where a number of them ate. drank, and slept.”

David Latimer who had passed away in 1881 at the age of 85, had, before his death, relating to the Rev. Whitehead the stories he had been told in his youth by eyewitnesses to the Prince’s arrival at Brampton in Cumbria. (The Lonnings are an ancient network of paths that traverse the hills of Cumbria).

‘There was at that time no other entrance into Brampton from Carlisle than “down The Lonning” and to persons coming that way into the town, the chapel of the almshouses, on the site of which now stands the parish church, would be almost the first building which presented itself to their notice. The Prince selected for himself the house now occupied by Mr T. Hetherington, in High Cross Street; the stables adjoining which have only of late years ceased to be called ‘The Cavalry Stables’. Another house in the same street, to this day known as ‘The Barracks’, by its name hands on the tradition of the use to which once it was put.

The Prince was anxious that his troops should be on their best behaviour during their march southwards, and not unnecessarily molest the inhabitants of the districts through which they had occasion to pass – a line of policy which most his officers, and the more intelligent of his men, constantly followed. Sergeant Clark, of Brampton, now in his 83rd year, says that when he was a boy a friend called Mary Gardner, who was eleven years old in 1745, related to him that one day, when Lord George Murray (a Jacobite Soldier and Commander) and his staff were dining at her father’s farmhouse at Westlinton, some Highlanders looked in, but seeing who was there, backed out. When Lord George and his party had finished their dinner, they asked what they had to pay. On being told they had nothing to pay, “Well”, said his lordship, “I believe we have saved you more than we have got”. Host and guest, no doubt, parted very good friends. However, some of the rank and file, unless they have been maligned, were not content with dining off what was set before them in the other farmhouses which they had visited. The late T. Routledge, a currier from Brampton, who died in October last aged 78, told me that he remembered having heard his grandmother say that she and other children were “sent off to Nether Denton to be out of the way of the Highlanders”. She did not tell him, however, and perhaps never knew, the fate to which they were supposed to have been in danger. It was, in fact, believed that the Highlanders were cannibals. If the sending away of children from Brampton was an unnecessary measure, the precaution taken by Mr Bell, of Townfoot Farm, as related by his great granddaughter, was not out of place. He hid his silver plate in a draw-well. Many families in the northern counties had a tradition of burying their ancestral plate in 1745, for fear it would fall into the hands of the Highlanders. Churchwardens too, in many places, concealed their communion plate; as at Penrith, where church accounts record “expenses for securing church plate in rebellion”.

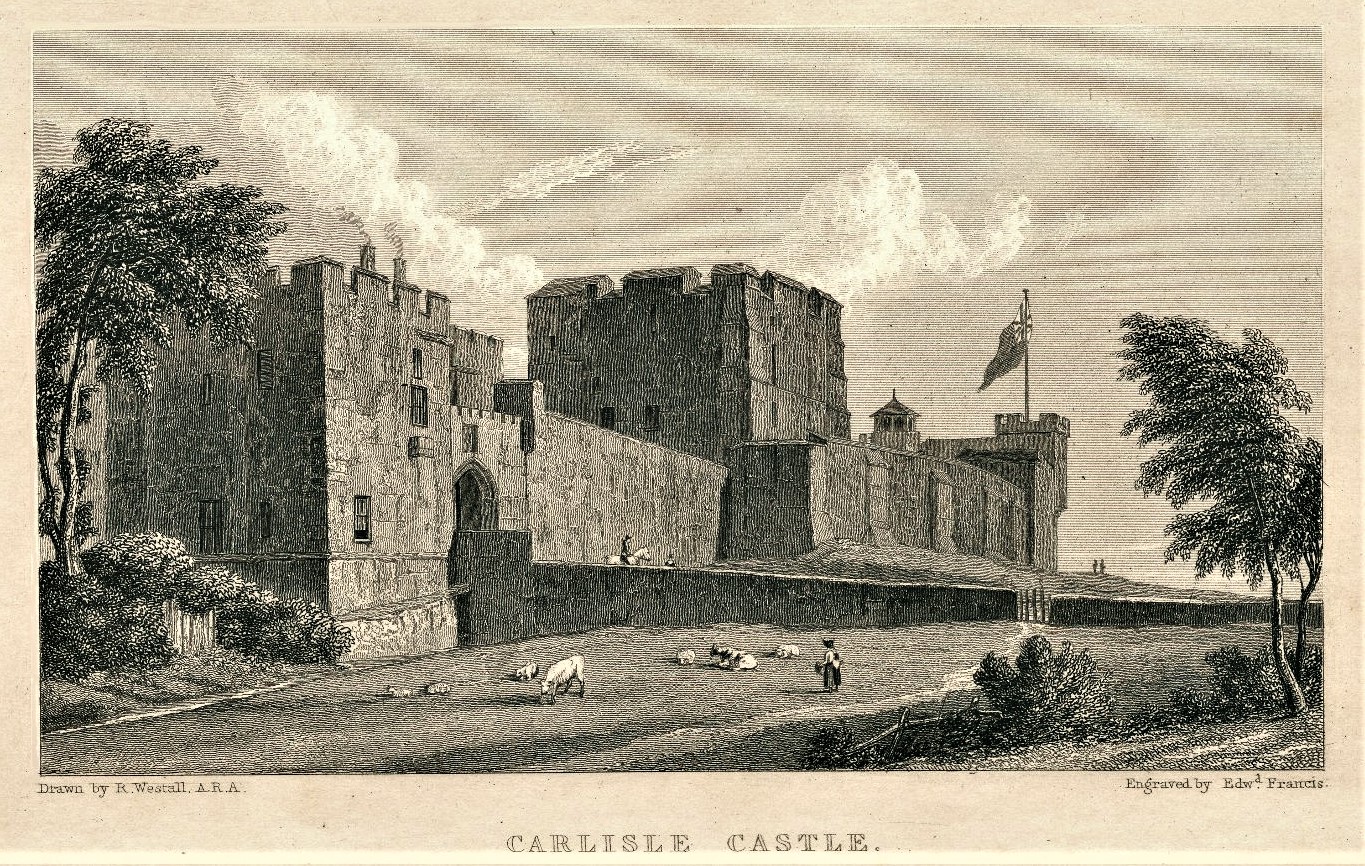

Having briefly alluded to the siege and surrender of Carlisle, the lecturer remarked that the surrender was greatly against the will of Colonel Durand, the Castle garrison, and the majority of the citizens, and some of the militia officers. One of whom, Joseph Dacre of Kirklinton Hall, recorded that, “when the health of the Prince Regent was drunk in the Market Place by the Highlanders, we deliberately proposed the health of King George.”

The Rev. Whitehead read a number of extracts from the Prince’s Household Book, showing the provisions which were purchased in Brampton, upon which he remarked that it was evident that the Prince, unlike the marauders who are alleged to have shot sheep and geese, regularly paid for all that he and his life-guards consumed. That a “good deal of unauthorised foraging was done by some of the rougher sort of his followers” is confirmed by the traditions of many of the farmhouses in the neighbourhood of Brampton. But those traditions are comparatively silent about plunder of any other kind. At Naworth Castle some of the Rebels left behind them halberd (a large, two handed axe), pike, and javelin. They seem to have had a habit of leaving such things behind; for at the Half Moon, Brampton, then kept the great-great grandfather of the present landlord, Mr Thomas Thompson, where, according to tradition in Mr Thompson’s family, eight troopers were quartered, one of them left a sword, which has ever since remained there. It is what is called a ‘dress sword’, one worn by officers at balls and on State occasions, and may therefore have belonged to someone of distinction, of whom there was no lack in the Prince’s army. A visit to “Squire Warwick’s House” is mentioned in the Household Book. This visit was no doubt, says Mr Mounsey, “on the 13th, the day of the muster at Warwick Bridge”. The squire, though a Jacobite and a Roman Catholic, was prudently “out of the way”, leaving the Prince to be entertained by his wife, “a daughter Thomas Howard, of Corby Castle, of a family which had fought and bled for Charles the First.” So pleased was the Prince with his reception at Warwick Hall that “he observed that these were the first; Christian people he had met with since he had passed the Border”.

Bearing in mind that remark, we must assign to a later day in the same week, a visit which the Prince is alleged to have paid about that time to another Jacobite family. The late W. H. Henfrey, the well-known numismatist (a collector of currency), wrote to me some years ago, stating that there was a tradition in his family, corroborated by letters and other documents in his possession, that his great-great-grandparents, whose name was Hetherington, but whose residence he only knew that it was somewhere in Cumberland, had “on one occasion entertained Prince Charles Stuart in the ‘45”, and that the Prince had “asked him to aid him in his endeavour to localise them”. This led to my having much correspondence with Mr Henfrey, who. in one of his letters, said “Mrs Hetherington, who was great Jacobite, subsequently left Cumberland and came with her daughters (she had no son) to reside in London. She was a great friend of Lady Primrose; and both ladies hid and entertained Prince Charles Edward when he paid his secret visits to London”.

Although Prince Charles Stuart had been forced to escape to France following Culloden, he always intending to mount another campaign. He did manage a secret visit to London in disguise in 1750, where he stayed at a house in Essex Street.

It was at this address that Mrs Hetherington was privately presented by Lady Primrose, “in her dressing-room, to Prince Charles Edward Stuart, during his short, secret, and stolen visit to London, between the 5th and the 11th of September, 1750”. Although the Prince was enthusiastically received and handsomely entertained during this visit, his intention to raise support for another uprising (known as the Elibank Plot) ultimately came to nothing.

Mr Henfrey continued, “It is now known for certain that on one of those visits he was formally received into the Protestant faith at the church of St. Mary-le Strand. I have an independent family account of this interesting occurrence; which Mrs Hetherington greatly assisted in bringing about. I have the Bible the Prince used on the occasion”. In another letter he informed me that Mrs Hetherington’s eldest daughter, Ann, who was married to his great grandfather, a Captain in the Guards, at Hampton Church in 1770, used to describe how, “she remembered kissing the Prince’s hand, with great ceremony, when she was quite a little girl; when she noticed the webbing of his fingers, although he wore long ruffles disguise it”.

Near Warwick Bridge, on Wednesday the 13th, while the Prince was dining at the hall close by, there was busy work going on, exacted from unwilling hands in the neighbouring woods. The Carlisle Patriot of February 24, 1821, in its obituary column had the following paragraph:— “At Brampton, Sunday last, at the extreme age of 101, Mr John Howard, Carpenter. During the rebellion of 1745 he was pressed by the Rebels, who conveyed him to Corby, and there compelled him to make ladders, with which they designed to scale the walls of Carlisle. Whilst engaged in this employment, he saw Prince Charlie, and picked up from various sources considerable information as to that young adventurer’s operations, which he was fond relating to the day of his death.” That Brampton carpenters were taken by Highlanders, on November 13th, to Warwick Bridge, and forced to make ladders, is a historical fact, recorded by the Gentleman’s Magazine of the period in its Advice from the North column. The fact was also attested by Mr lsrael Bennett, formerly Presbyterian minister at Brampton who, before November 1745, had removed to Carlisle. The reason why the Highlanders were under the necessity of having new ladders was because there were none at hand for them beg, borrow, or steal, Colonel Duran, having taken the precaution of requesting the County Magistrates “to issue warrants for bringing into Carlisle all the ladders within seven miles round and further, which was immediately complied with, and the ladders were brought in”.

Miss Lydia Hewitt, of Brampton, now in her 84th year, says she had long in her possession an account which her father had written of his adventures whilst with the army. Miss Hewitt, who, in her 17th year, heard part of the story of the ‘45 from her father, about the men who made ladders for Prince Charlie. Another Brampton man, who was a reputed centenarian, was in 1745 among the Militia at Carlisle. The famous Robert Bowman, whose epitaph in Irthington Churchyard states that he died 18th June 1823, at the patriarchal age of 119 years. His experiences as a defender of Carlisle were thus related by himself to the late Mr Robert Bell of Irthington – “The cannon balls from the Highlanders were coming rattling into the city from Stanwix Bank like hail, and besides we were starving of hunger. For my part I had nothing but a basin of broth for three days, so in the night I scrambled over the city wall and cut off for home”.’

However, it appears that Robert Bowman’s account of the battle may have been exaggerated to help justify his decision to desert. Rev. Whitehead in his lecture then produced a statement written by a Mr Robert Campbell before he had passed away. The 81-year-old locksmith from Argyllshire remembered his father, also named Robert, had joined the Prince’s army at the age of 16 and, as one of the besiegers of Carlisle, they “did not discharge a single shot, lest the garrison should become acquainted with the smallness of their calibre, which might encourage them to defend themselves”.

___________________________________________________________________________

Returning to the story in The Carlisle Patriot from March 1887,

‘Talking of Argyllshire, Brampton parish register for 1745 has the following entry:—”Nov.13th, John, son of Archibald Henderson, Argyllshire, baptised”. From which it seems that one of the Prince’s soldiers was accompanied by his wife; and if so, the baptism of their son, perhaps in the chapel of the almshouses, where some of the troops were quartered, would be home for an interesting episode in that eventful week. The vicar, Mr John Thomas who baptised this child, had evidently not thought it necessary to leave the town because of the presence the invading army. “Of course not”, it may be said! That may be so but the records of Brampton Presbyterian Church, in 1745. contain this memorandum: “November 10th and 17th. No sermon, the Minister being out of ye town because ye rebels were in it.” The minister seems to have been in rather in hurry to get out of the town; for by the first of those two Sundays, Nov.10, only a few straggling Highlanders could have arrived. Nevertheless, it was noted that on “Nov.17th there was no sermon or Sunday service of any kind, and there was difficulty about praying for King George. After the Rebels got possession of Carlisle I was detained in town till near night on Sunday, the 17th, to try and find out whether they would allow prayers to be read in the churches without naming the King. This was “absolutely refused”. There were two messages, one from the Pretender and one from the Duke of Perth, for that purpose”. The Prince, it appears, would bear him no malice, even if he did pray for King George. When in Edinburgh to punish Mr McVicar, the minister of the West Church, who not only prayed for King George, but stoutly asserted his right to the throne, Prince Charles Stuart replied that “the man was an honest fool, and I would not have disturbed him.” Most persons will probably say, along with Sir Walter Scott, that they “do not know whether it was out of gratitude for this immunity” that Mr McVicar, the following Sunday, after praying as usual, for King George, continued: “As to this young pretender who has come among seeking an earthly crown, do Thou, in Thy great mercy, grant him a heavenly one.”

Some accounts of the ’45 represent the Prince as having made his entry into Carlisle on November 17th. But it is clearly shown by his household book that he spent that Sunday in Brampton. It may therefore have been that day that he received the keys of Carlisle from the Deputy Mayor Mr Pattison and, some say, the Corporation. An eyewitness, however, of that imposing ceremony, Elizabeth Smith, who died in 1813, aged 89, and was therefore 21 years old in 1745, told her grandson, George Hetherington, who died in January 1881, aged 83, that Mr Pattison was only accompanied by two members of the Corporation. Mr Hetherington, who was 16 years old when his grandmother died, told me that she was fond of describing the crowd and commotion in High Cross Street on the occasion of the delivering up of the keys to the Prince. Among that crowd she well remembered having seen one Margaret Ewing, a girl of 16, who had come with the army from Scotland. That girls did accompany the army we know from what is recorded as having happened at the crossing of the river Esk, then much swollen from recent floods, on their way back to Scotland: “None were lost, except for a few girls, who, for their love of the white cockade had followed the army throughout the whole of its singular march, with heroic devotion which deserved a better fate”.’

It appears that the otherwise loyal Jacobite Margaret Ewing chose to stay behind in Brampton when the Highlanders returned to Scotland. She “voluntarily chose to be the girl they left behind them” is an odd phrase from the records, which does not tell us why she made that decision. However, the Penrith parish register of 1748 does carry this entry: “Dec. 28, John Richardson and Margaret Ewing, both of Brampton, married”. John Richardson belonged to an ancient yeoman family from Brampton and possessed a small estate at Easby, comprising 40 acres, He died in 1799, aged 73. Margaret Ewing (or Richardson) was, by all accounts, a notable woman. Her Brampton contemporaries firmly believed her to be of noble Scottish birth.

The Carlisle Patriot continued, “But if so”, says the local record, “she kept her secret well, she was in no way communicative to those about her”. Margaret died in 1813, aged 84, leaving the estate to her grandson and it is said it she left it him on the condition that he inscribed her the following epitaph:

“Here rest my old bones; my vexation now ends

I have lived far too long for myself and my friends.

As for churchyards and grounds which the parsons call holy,

‘Tis a rank piece of priestcraft, and founded in folly.

In short, I despise them; and as for my soul,

It may rise the last day with my bones from this hole;

But about the next world I ne’er troubled my pate;

If no better than this, I beseech thee, O Fate,

when millions of bodies rise in riot,

O, pray, let the bones old Margaret lie quiet!”

The penultimate line seems to indicate that Margaret had no wish to be awoken by another Jacobite rising, which she surely believed would come! The record goes on to state that, “the then vicar of the parish, his attention having been brought to this epitaph, sent a copy of it to the Chancellor of the Diocese, who at once hastened Brampton, and actually stood over the mason, one George Rowell, until he had removed the objectionable lines with a chisel and mallet”.

‘That the vicar knew nothing about this epitaph until his attention was called to it, may to some appear strange. However, the churchyard is a mile and a half from the church, vicarage, and town, and in later times many a tombstone has been placed there without the knowledge of the vicar. The Chancellor of the Diocese, if the above story be substantially true, must, I think, have ordered the stone be altogether broken, for the stone which now surmounts Margaret Richardson’s grave does not look if it had ever borne any other inscription than her present epitaph, which consists of ten ponderous lines, orthodox enough to have been composed by the Chancellor himself.

Almost as mysterious a personage as Margaret Richardson, and equally reserved about his private history, was one Lachlan Murray, of whose ancestors nothing was ever known beyond the fact of his having come from Scotland in the ’45. Tradition is silent as to whether he left the army during the siege of Carlisle, or during its retreat from Derby. It is certain that he did not return to Scotland, but settled himself at Irthington, 21 miles from Brampton, where he kept school, taught land surveying, and became in 1755, or thereabouts, parish clerk. He died in 1801, aged 80. Lachlan Murray must have gained a great reputation for versatility of talent, for in 1788, as shown by the churchwardens’ accounts, he was entrusted with the work of “drawing plans for the new church”. The worst thing known about him is that he could not, at all events did not, prevent his wife, who kept the grocer’s shop, from using the leaves of the parish register as wrappers for tea, cheese, and tobacco. There is, therefore, now no register of an earlier date than 1704; and there is a gap from 1722 – 1729.

Less reticent about himself than Lachlan Murray and Margaret Richardson was one Richard Wallace, who said he was brought as a child from Scotland in 1745 by his father, who, he said, was killed at the siege of Carlisle; when (Richard) was taken charge of by the Carlisle parish authorities. He was, by then, apprenticed as a tailor; and when out his time was served he settled at Boothby, in Brampton parish. He was buried, according the register, on Feb. 9th 1835, aged 89; which would make him to have been, at the utmost, ten months old at the date of the siege of Carlisle. His father was certainly not the one man killed during the siege, who was known to have been a Frenchman. But may have been one of the soldiers left by the Prince to garrison Carlisle, and then taken prisoner when the city was retaken by the Duke of Cumberland. It is on record that in the latter end of July (1746) a number of the prisoners taken at Carlisle on its recapture, who had then been removed to Lancaster, were sent back to Carlisle, in order to face their trial at assizes; amongst whom, condemned to death on September 23th, was one John Wallace. If, then, John Wallace had really brought a child with him from Scotland, the child, on the re-capture of the city, would doubtless have been taken in hand by the parish authorities, from whom in later years be would learn his own strange history. There remains the difficulty in believing that any soldier engaged in such an expedition, would have brought with him as young a child. It can be presumed however, what with Margaret Ewing and other girls, the child, even if motherless, would not want for nurses. A further difficulty arises from Richard Wallace having told his grandchildren, Thomas Wallace now 69 years old, and Mrs Appleby, now 75, both of Brampton, that he remembered having heard the Cathedral bells ringing on the occasion of Prince Charlie’s entry into Carlisle. If so, he must have fallen into the mistake, usual with old people, of understating his age. More probably he only remembered having heard people talk about the ringing in of the Prince, and supposed he had heard the bells himself. Referring to this tradition myself, in my paper The Bells of Carlisle Cathedral, I said that “one would think they must have been rung when the city was recaptured by the Duke of Cumberland”.’

It is truly fascinating to recount the Prince’s siege of Carlisle, and its ramifications, from the mouths of those present and to learn some interesting personal details which would perhaps otherwise have been lost in the mists of time. My personal favourite is the barbed epitaph left by Margaret Ewing, who feared a further rebellion; perhaps fearing reprisals for her part in the ’45.

Mark Bridgeman