The 31st December 2020 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. To commemorate this special occasion the West Highland Museum has organised a series of articles written by scholars, academics, authors, and Jacobite enthusiasts. In this seventh in the series, local historian Kenny MacIntosh focuses on the story of Ranald MacDonald, the son of Major Donald MacDonald of Tirindrish.

The Aftermath of the Rising in Brae Lochaber

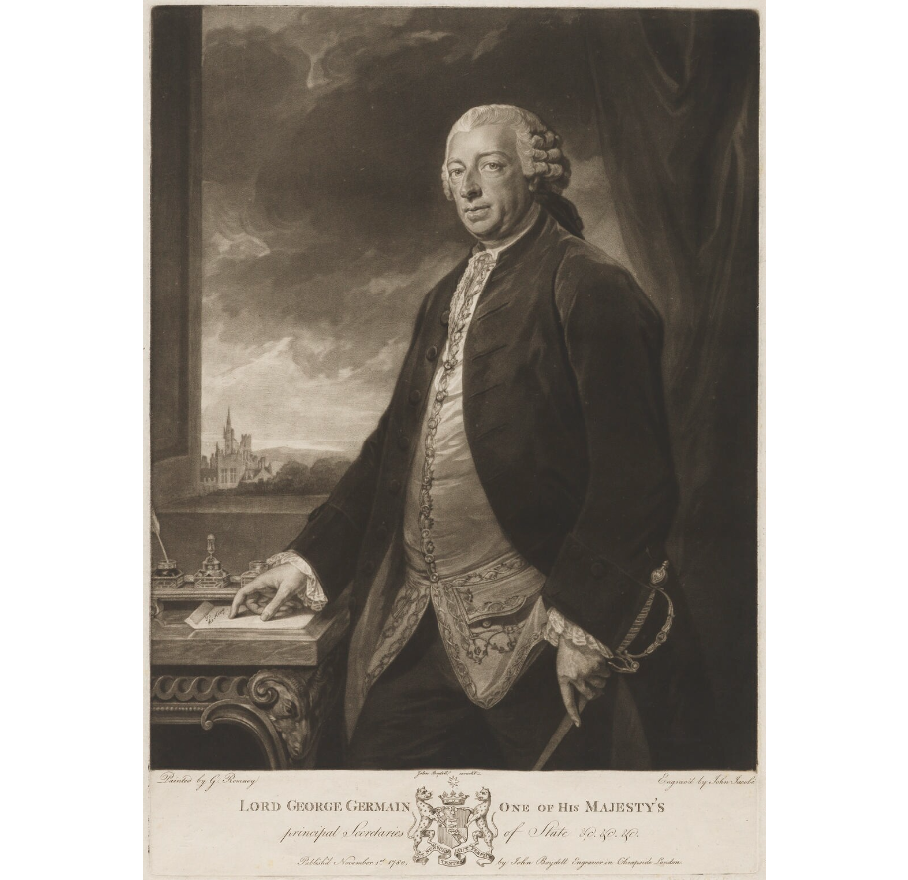

Ranald MacDonald the son of Major Donald of High Bridge fame was a seven-year-old boy at the time of the defeat at Culloden in 1746. He was forced to flee his home at Tirindrish beside Spean Bridge as British troops under direct orders from their Commander, “Butcher” Cumberland systematically rampaged among the now defenceless civilian population of the Jacobite heartlands. Ranald’s family were reasonably well connected but still suffered dreadful privations and were fortunate to escape the clutches of the psychopathic Lord George Sackville (Lord George Germain from 1770) and his 20th Foot Regiment who burnt Tirindrish House whilst laying waste to Lochaber.

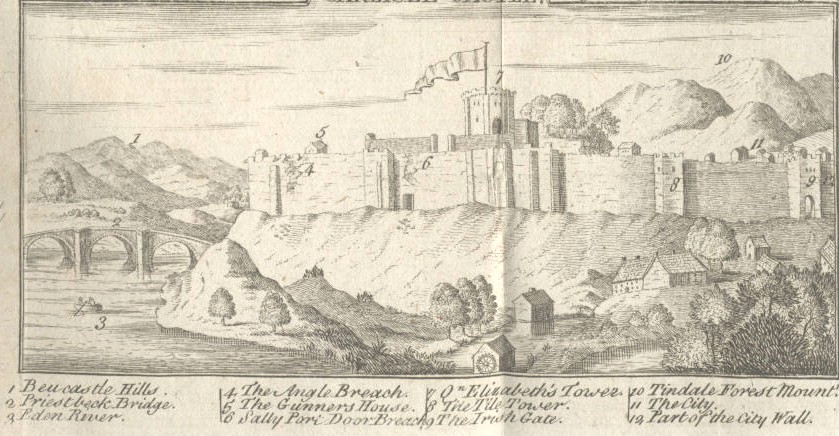

The fate of the common people was much worse, with nowhere to turn, they were subjected to every kind of brutality including murder, torture, rape, robbery, starvation, imprisonment, summary execution, at the hands of the British Army. Their houses were destroyed, crops burnt, animals driven off, food supplies stolen, followed by the enactment of repressive laws designed to eradicate their language and culture and a resurgence of religious persecution. Even in those far-off days such behaviour by a Government towards its own subjects was considered disgraceful. Hanoverian apologists tend to say that this was standard practice for the times, but significantly, German mercenaries in their hire were so disgusted by their cruelty that they refused point blank to participate in the atrocities. Cumberland himself is recorded as seriously planning to forcibly uproot the entire Highland population of Lochaber and transport them to the Colonies. Ranald’s father, the gallant and humane Major Donald, was captured by accident at the Battle of Falkirk and imprisoned at Carlisle before being convicted at a mock trial and executed in a horrific manner.

The family found themselves fleeing to the remoteness of Loch Treig to be sheltered by MacDonalds of Fersit, one of whom had just escaped from the Culloden disaster, and joined the desperate bands of refugees hiding out in the inhospitable wastes of Rannoch Moor. An element of the Highland Militia employed by the British had more sympathy for their countrymen than for their paymasters and were to provide some protection for the fugitives. Eventually they were able to make use of a Jacobite underground network which saw them stay for a while at safe houses in Edinburgh, Carlisle, and Traquair en route to permanent protection at the home of a leading English Catholic family at Warwick Hall in Cumbria. The Tirindrish family were Roman Catholics, as were the rest of the Keppoch Clan, and after schooling in England, where he had to relinquish his Gaelic language or “Erse” as he refers to it, Ranald was drawn to the priesthood. He was enrolled in the Scots College seminary at Douai in France and tragically died just before his ordination. This is his own story written as 9 year old schoolboy.

THE ADVENTURES OF RANALD MACDONALD

FROM SEVEN YEARS OF AGE TILL HIS ARRIVAL AT WARWICK HALL.

Written by himself, A.D. 1749.

―After the battle of Culloden, the cruelty of the soldiers made us fly from our houses; and the first night we went and drove all our cows and sheep about two miles from the house, and carried all our provisions upon the horses, our bed-clothes, and all the other goods in the house, to the place where we took our nights lodging, and pulled ling to make a fire and beds of, and we laid beside a little water that was at the bottom of two hills. Early next morning we went to Loch Traigh, and it was six days before Ronald Angus came home; everybody thought he was dead. My stepmother came to the other side of the loch to see her sister, and call at Ronald Angus‘s house, which was two miles from the place where her sister lay ill of the small-pox, and Ronald Angus‘s maid went along with her to see her sister; and when I was coming home I felt a pain in my back, and could not walk home. But the maid carried me, and they put me to bed, and I was very bad of the small-pox. They had no whisky in the house, or they would have given me some. I was blind about a week, and one day I began to see the walls; then I got up, and was very well. Then we went to Ranach, to get further from the soldiers, whom we heard were near hand us. I went along with my stepmother. My eldest sister and a gentleman went along with us; four servants and my two youngest sisters went with the cows, sheep, and goats, and drove them to Ranach. My stepmother, the gentleman, my eldest sister, and me, went to Ranach through woods and over mountains on foot; and we used to lie on the tops of the mountains, and the gentleman used to roll me in his plaid with himself, and sometimes we walked all night when we heard the soldiers were near us. Upon a hill we spied our chief s son and all Keppoch‘s family, but we had very little time to stay with them, for we heard the soldiers were coming that way. Then we parted, and travelled all that night on foot, and the next day till seven o‘clock in the evening. Then we took our night‘s rest under two steep hills, where we had four miles to go for wood to build a little house of sticks and sods, and we had as far to go for water as we had to go for wood. When we were about three days at that house, to our surprise we saw three men at the top of the mountain, and it proved to be Ronald Angus and his brother Samuel, and another man with them. They all three came into the house, and took me to Ronald Angus‘s house. ―We set forward about six o‘clock in the morning, and they got me a little galloway, and they went themselves on foot, and they ran all the way as the galloway trotted; and about eight o‘clock we got to our journey‘s end, where we saw a drove of cattle and some gentlemen that had been along with the Prince, flying from their houses. We made little houses, where we put our milk and curds, for we made cheese when we were not travelling. ―When we had stayed there about two days we heard the soldiers were coming that way. Then we went to a wood, where we built a little house, and stayed there about a week; and there was a loch near the wood, where Samuel Angus used to fish, and struck fire with his flint to make a fire to broil them. Then, as we had heard that the soldiers were gone, we travelled home again, and drove our cows and sheep over a river, and on the other side we built a house, and we stayed there about a fortnight; then we set forward for Loch Traigh. When we came within sight of it, I asked them what they called that loch, and they told me, and I could scarce believe them. We stayed in a wood on the other side of the loch about four days. Then we went to Ronald Angus‘s house, and stayed there about a fortnight; and there is a river runs out of Loch Traigh, and in the middle of the river an island, where the cows used to graze. I was sent to drive them back; so I stript to wade over the water, but it was so deep that it came into my mouth, and I stumbled in the middle of it, and had like to have been drowned, but Samuel Angus came and saved me. And there came some militia that got all their victuals from Ronald‘s, and they got a house on the other side of the water, where they lodged; and they said that if any of the soldiers came then they would not let them meddle with us. ―I went to see them before they went away. The head of them gave me a shilling, and I gave it to Ronald‘s mother. Then my stepmother came to Terndriech, and when she saw her house was burnt, she built a little house of wood and turfs. A little after I heard I was to come to a gentleman‘s house in England, and two gentlemen had come to meet me. In the afternoon, my uncle and a lad that could talk English, and us, we all went to Ronald Angus‘s house at Loch Traigh, about fourteen miles from my father‘s house, all night. We set out about eight o‘clock next morning; then we travelled to Ranach. Ronald Angus and Samuel and another man set us twelve miles, and Ronald Angus and Samuel and the other man then took their leave of me. ―Then my uncle and the lad and myself went to a gentleman‘s house, where we met Mr. Rose and Mrs. Douglas, and another gentleman with them. Mr. Rose could speak Erse. We stayed at that house all night. The next morning my uncle took his leave of me, and returned home. That lad still went along with me till I came to Edinburgh, and I got English clothes, and I did not love myself in them. I went one day to see a lady, and she gave me a guinea; and as we were coming home Mrs. Douglas called at a house, and she bade me let her see it. I thought she only wanted to see how much it was, but she put it in her purse, and I never saw more on‘t. As we came home she carried me to the castle to see Glengarry, and I went to Glengarry‘s room, and a little after Glengarry went downstairs, and his man called to me in Erse; and there was a soldier stood guard at the door, and he said, ‗Come back again‘, and I did not know what he said, but I heard some people say, ‗No‘, and I said ‘No‘, and ran downstairs. Then Mrs. Douglas and I went home, and set out for Carlisle in the chaise, and we dined with some French officers at Carlisle, and then we went back again to Edinburgh, and then I stayed there about a fortnight.

Then Mrs. Douglas and I went to Traquir, about fourteen miles from Edinburgh, and I stayed there about eight months, and I went to school, and my cousin learned me English and I learned him Erse. And when I was there about eight months, a man came for me, and he came to Enderlithen for me, and the master gave up play all that day, and Sharp got a fiddle and played all the day almost, and we danced country dances and reels. Then I took leave of all my acquaintances. We were three days on the road, and the houses that we were at all night they were very civil to us, and they got a fiddler, and we danced till after ten o‘clock; and there was a young man that I knew that I laid with all night; and we got up early next morning, and we got to Langam at three o‘clock, and we dined there, and we could get to Warwick that night. But Sharp thought that it would be too much for the horse, and we stayed at Langam all night, and next morning we came to Warwick, where I was kindly received.

Kenny MacIntosh