The 31st December 2020 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. To commemorate this special occasion the West Highland Museum has organised a series of articles written by scholars, academics, authors, and Jacobite enthusiasts. In this second in the series historian Deborah Dennison examines a waistcoat in our collection with a special family connection.

The Prince’s Gift

It seems an odd sort of gift – a piece of clothing that you’ve worn which could not possibly fit the recipient. And yet it is not uncommon to find enshrined exhibits of clothing worn by the royal and famous which were bestowed on honoured friends and followers. The practice seems to lie somewhere between sacred relics and mementoes from friends.

When Charles Edward Stuart embarked for Scotland, he carried with him a stash of gifts to bestow on the loyal and deserving, and collections of these include snuff boxes, rings, and objects bearing the many symbols of Jacobite allegiance. But far more evocative seem to be the pieces of his own clothing which were bestowed on loyal friends by the Prince. I was lucky enough to attend a talk given by the tartan expert Peter Eslea MacDonald in which he brought along an authenticated piece of the Moy tartan. The Prince’s DNA is likely on this, Peter told us. There was a gasp among the assembled listeners as we carefully passed around the box containing the fragment. Snuff boxes may be more valuable in a material sense, but the potency of ‘this was mine, now it is yours’ seems to carry its own special mystique.

As is often pointed out, Flora MacDonald was not, by family allegiance, a Jacobite, but belonged to a distinct minority of Clan Donald who did not ‘come out’ in 1745. Still, she carried with her for the rest of her life the bed sheet on which Prince Charles Edward slept the night before they left for Skye and insisted that it be her shroud. Despite recent attempts to disparage him, the Prince’s own charisma, courage, and compassion – attested to by so many who knew him – is clearly part of the reason for this veneration of material personally associated with him.

It is important to remember, however, that the possession of objects with Jacobite association could find the owner under charge of sedition or treason. In most of the Western world today, we are accustomed to openly expressing our political views, often in outrageous charges against parties and politicians in print and online. It may be hard to comprehend that just being overheard toasting ‘the King Over the Water’ could land you under serious charges in court. As Murray Pittock writes in his remarkable work: Material Culture and Sedition:

‘The major threat to Jacobite discourse, language, symbol, association, connection and display were the laws on treason and sedition. These could be very severe in their effects, not infrequently bearing the risk of a capital charge.’

The risk also existed in the places of Jacobite exile in France and Italy. These locations were crawling with British Government spies. The possession of a ring inscribed with the motto ‘dum spirat spero’ might not find the wearer up for hanging, drawing and quartering, but his family and friends in Scotland, England and Ireland could suffer for it.

In this context, a piece of clothing, a tartan plaidie, a worn cota gearr tucked away in the bottom of a coffer could be passed on through the family with its secret, but not endanger the owner. This of course creates a serious headache for museum curators and auction house specialists looking for provenance.

If the story that accompanies this beautiful waistcoat holds, the garment must have been given to Dr. Irwin by Charles Edward before he left Rome in 1744. Charles did not return to Rome until after the death of his father, by which time Dr Irwin was also dead. Although the Prince would have known Irwin through his childhood, given the adult size of the garment, it must have been bestowed upon the doctor shortly before Charles left Rome, in complete secrecy, in the small hours of a cold January morning in 1744.

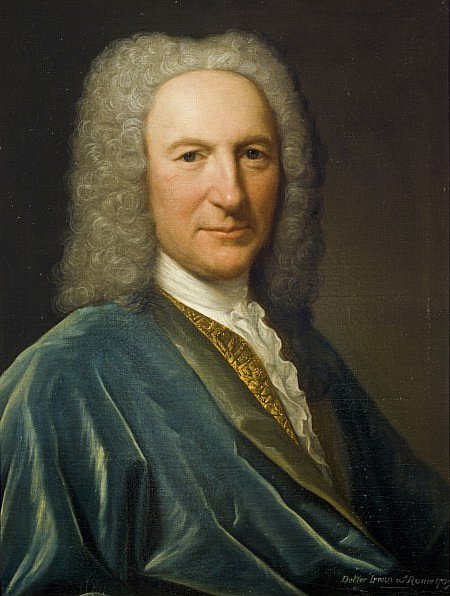

When I first saw the waistcoat many years ago at the Museum, I recall the display explained that it had been as a gift from the Prince to Dr. Irwin. My heart skipped a beat because, by family legend, my grandmother Irwin was descended from the good doctor. We knew they were Jacobite Episcopalian Scots who were as unwelcome in Georgian Scotland as the Jacobite Catholics on the other side of my father’s family. Discerning the nature of Dr. Irwin himself is a bit tricky. The National Gallery note that the artist identified the portrait as Dr. John Irwin and accompany his portrait with this colourful description:

‘Dr Irwin was one of the physicians appointed to attend the Jacobite court in Rome and he was well-known in social circles there. Scottish architect Robert Adam met him about fifteen years after this portrait was painted and described him as: “a very sensible, clever old man of near eighty years who every day drinks his four or five bottles of wine, has a flow of spirits meet for forty years and does not look sixty.”’ This painting is one of several painted by Dupra of prominent Jacobites in exile. As with the other paintings in this series, Dupra left an inscription on the back of the canvas giving the name, date and referencing the Jacobite cause.

Prof Edward Corp, on the other hand, lists the good doctor as Dr James, not John, Irwin and notes that as James VIII’s health began to seriously fail, Cardinal Henry, Charles’s alienated younger brother, insisted that his father be attended by Italian doctors rather than the Scottish physicians (which Henry curiously calls ‘English’). Corp further tells us that Irwin objected to the extensive bleeding the Italian doctors prescribed and angrily stepped aside at Henry’s insistence.

Examining the piece itself reveals something of the owner. It is a creamy white silk with wonderfully fine embroidery and beautifully made matching buttons. But it is very restrained, especially for a prince of the blood who lived in an extravagantly Rococo Italy. We can only surmise why Charles would have given it to Dr. Irwin, but there are plenty of clues.

Unlike the House of Hanover, the later Stuarts were affectionate and loving parents. It is clear that Charles and Henry were loved by both James and Clementina and that that affection was returned by both boys. But the terrible politics which reigned destruction and havoc on the Stuart Court, largely around matters of religion, created an exceptionally difficult environment for a young boy, culminating with the death of his mother when Charles was still young. The power struggle between the Vatican and the influential Dunbar and Hays, turned a dispute over the religious environment of the two Princes into an all out war between James and his wife. James wanted his sons to be brought up by both Protestant and Catholic tutors and mentors. Clementina fought fiercely for an exclusively Catholic environment and education. The Pope himself actively meddled in the marriage, causing a serious alienation with the Vatican for the otherwise devout James. In Charles, this inculcated a deep resentment of the Vatican which would last all his life and would make his younger brother’s decision to become a part of it all the more painful. But Charles also blamed and disliked Dunbar. The nasty split between James and Clementina was doing serious harm to the support of European allies, and Charles was well aware of this. The Palazzo Muti was crawling with spies and informants who reported every detail of this rift to a gleeful Walpole.

In addition, James clearly believed that the best parent is one who offers correction far more often than praise. Young Charles excelled in riding, shooting, dancing, played several musical instruments well, was praised for being clever, gracious, generous, and having a princely baring by everyone, except his father. His mother had retired to a convent to fast and pray and he often spent long periods without seeing her. So it is not surprising that Charles would form attachments to his tutor, Thomas Sheridan, and, perhaps, also to a friendly doctor always willing to listen over a glass of wine, to whom Charles gave a beautiful personal memento as a parting gift.

Sources: Bonnie Prince Charlie, Charles Edward Stuart, Frank McLynn

Fight for a Throne, Christopher Duffy

Material Culture and Sedition, Murray Pittock

The Stuarts in Italy, 1719-1766, A Royal Family in Permanent Exile, Edward Corp

The National Portrait Gallery online archives.

Deborah A. Irwin Dennison