The population of St Kilda, before the island’s evacuation, survived mainly on seabirds and their eggs. Because fishing in the waters around the archipelago was often hazardous, and the soil too poor for all but limited agricultural, the islanders often risked the short but dangerous boat trip from the main island of Hirta to the Stac an Armin, a nearby imposing, craggy rock that jutted from the Atlantic. Here the men could catch gulls, fumars and collect eggs from the thriving colony on the rock.

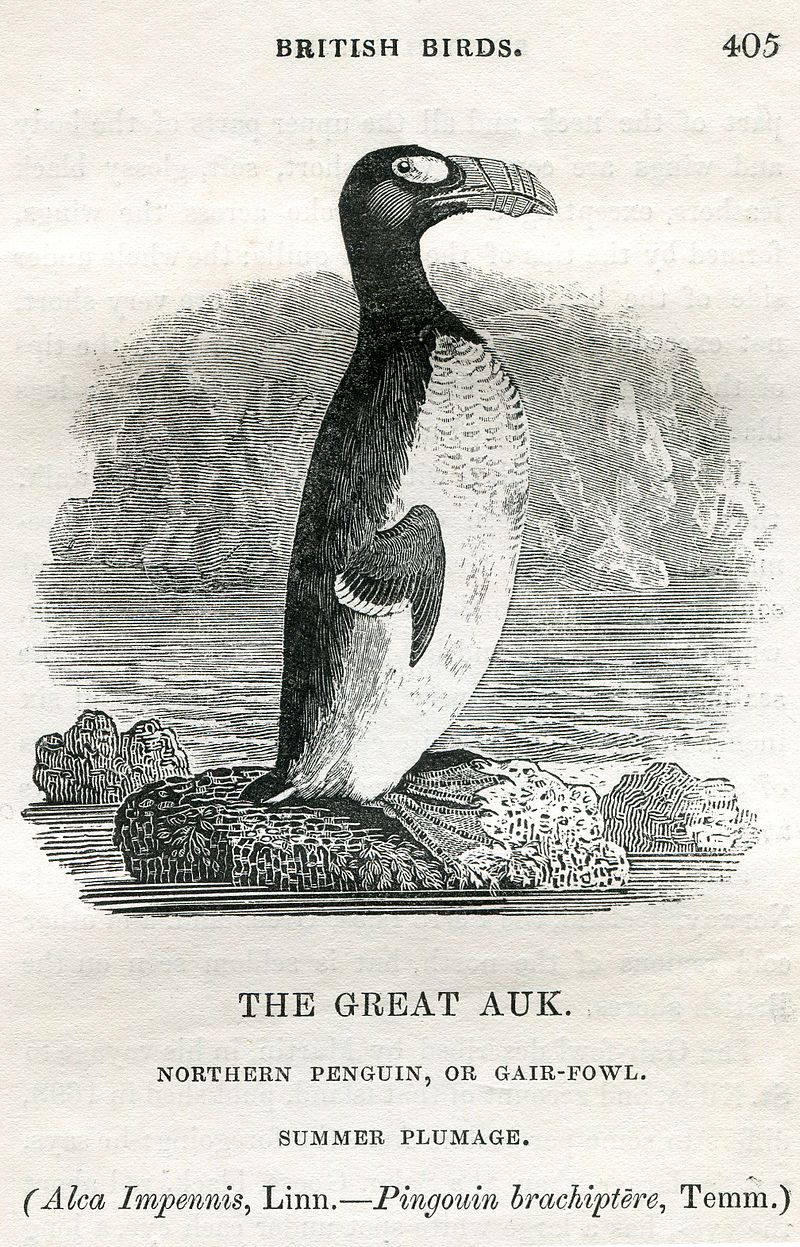

In 1840, while sailing towards the Stac an Armin, Laughlan McKinnon sighted a strange bird napping on the rock. The bird did not seem to resemble the other birds he had seen on the Stac, or in the waters around the island. It wasn’t a gull or a puffin. Plump, with a black and white belly, the strange bird stood three feet tall and had comically short 6-inch wings. Its black beak was heavy and hooked, with a grooved surface.

Laughlan McKinnon (had he known of their existence) might have been forgiven for confusing the bird for a penguin. The black-and-white creature was clumsy on land but a torpedo in the sea. It feasted on fish and had a low, croaking scream. It was flightless, monogamous, and nested in some of the world’s iciest, and most rugged, territory. Both parents cared for the eggs, and with little experience of man, the bird was entirely unafraid of people. Scientists would name the bird Pinguinus impennis – or the Great Auk. When early explorers discovered flightless birds in the southern hemisphere, they called these creatures penguins because of their resemblance to the great auk. (The birds, however, are biologically unrelated.)

For centuries, great auks occupied the chilly islands near Iceland and Greenland, but this was the first sighting of one in the St Kilda archipelago. When not breeding, the Auks spent their time foraging in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as northern Spain and also around the coast of Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and the Scottish Islands. Prized for their meat, oil, and feathers, by the early 19th century the species had been slowly hunted to near extinction. Great Auks were hunted by Neanderthals as early as 100,000 years ago, as evidenced by well-cleaned bones found by their campfires. Despite their long persecution by man Great Auks had no innate fear of humans; a person could easily walk up to a bird and strangle it—and many did. In 1534, the French explorer Jacques Cartier wrote that he was able to fill two boatloads of dead Auks in just half an hour. He compared the activity to packing a ship with stones. In the days before ecological awareness the Great Auk was worth more dead than alive. Locals valued its meat, which fishermen used as food and bait. Sailors coveted the oil rendered from the bird’s fat. Pillow-makers prized the auk’s feathers. Both Britain and Canada passed conservation laws to protect the Great Auk, but sadly, as the bird’s numbers plummeted its value soared. Perhaps Laughlan McKinnon and his party recognised the value of the bird, or perhaps the bird was merely a curiosity to their group. Whatever their reason they made the unusual decision to take the bird alive: One of the men, Malcolm MacDonald, approached the snoozing bird, snagged it by the neck, and lassoed its legs together. Shocked and surprised the auk woke and began to wail. And as the bird screamed, so the party would later relate, rain began to fall. The rain soon turned into a howling Atlantic storm and the group decided to wait out the worst of the weather in a small stone bothy (known as a cleit) on the Stac; carrying the Auk inside with them.

The first day passed, then a second day. The storm continued to rage, and the swelling waves prevented the men from returning to their boats and heading back to the main island of Hirta. By the third day the men, still huddled in the bothy with the Auk, were beginning to become apprehensive about their fate. Meanwhile the terrified Auk wailed whenever any of the group approached it.

The St Kildans were superstitious, often assuming that bad weather or mishaps were an ominous omen. Legend tells us that the party finally determined that there was only one cause for their bad luck – the Great Auk. They quickly concluded that the bird was no bird at all, but an angry storm-conjuring witch.

Laughlan McKinnon quickly decided that the group had no choice but to kill the evil witch. According to one account, the men beat the auk with two large stones, another version claims sticks were used. As no trees grow on either Hirta or Stac an Armin stones seem more likely to have been their weapon of choice. Alas, the bird was killed, and the men eventually returned to Hirta, believing they had triumphed over the evil spirit. This was to be the last sighting of a Great Auk anywhere in the British Isles, and decades later, historians conjectured that this bird was almost certainly the last Great Auk in Britain.

Yet still the inevitable hunting continued driving the birds to the verge of worldwide extinction. In a last-ditch attempt to save the species a breeding programme was established on the remote island of Eldey, near Iceland in 1844. Sadly, the last breeding pair of the species would suffer a similar—though less superstitious—fate. The final mating pair of Great Auk was strangled to death by a group of fishermen on the 3rd July 1844.

At the very moment the fisherman struck, the female bird had been incubating an egg. As the men struggled to kill the Auk, one of the fishermen stomped on the egg with his boot, effectively crushing the future of the species.

Although rumoured that Great Auks were spotted in the North Atlantic in the 1850s, there has never been another confirmed sighting on St Kilda, or anywhere else in the world.

It is still possible to see the Great Auk, however, there are stuffed examples in the Natural History Museum in London and the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow. Both sit forlornly as testament to man’s cruelty to the natural world around him.

Mark Bridgeman

Mark Bridgeman is an author. His latest book “Blood Beneath Ben Nevis” is available at the Highland Book Shop (Fort William), Waterstones & Amazon. It will be available in the Museum shop from 1 September 2020.

Mark Bridgeman’s Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=mark%20bridgeman%20author&epa=SEARCH_BOX